-By Denise Grady July 14, 2014

SAN FRANCISCO — Minutes after a baby girl was born on a recent morning here, her placenta — a pulpy blob of an organ that is usually thrown away — was packed up and carried off like treasure through a maze of corridors to the laboratory of Susan Fisher, a professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences.

There, scientists set upon the tissue with scalpels, forceps and an array of chemicals to extract its weirdly powerful cells, which storm the uterus like an invading army and commandeer a woman’s body for nine months to keep her fetus alive. The placenta is the life support system for the fetus.

A disk of tissue attached to the uterine lining on one side and to the umbilical cord on the other, it grows from the embryo’s cells, not the mother’s. It is sometimes called the afterbirth: It comes out after the baby is born, usually weighing about a pound, or a sixth of the baby’s weight.

It provides oxygen, nourishment and waste disposal, doing the job of the lungs, liver, kidneys and other organs until the fetal ones kick in. If something goes wrong with the placenta, devastating problems can result, including miscarriage, stillbirth, prematurity, low birth weight and pre-eclampsia, a condition that drives up the mother’s blood pressure and can kill her and the fetus. A placenta much smaller or larger than average is often a sign of trouble. Increasingly, researchers think placental disorders can permanently alter the health of mother and child.

Given its vital role, shockingly little is known about the placenta. Only recently, for instance, did scientists start to suspect that the placenta may not be sterile, as once thought, but may have a microbiome of its own — a population of micro-organisms — that may help shape the immune system of the fetus and affect its health much later in life.

Dr. Fisher and other researchers have studied the placenta for decades, but she said: “Compared to what we should know, we know almost nothing. It’s a place where I think we could make real medical breakthroughs that I think would be of enormous importance to women and children and families.”

The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development calls the placenta “the least understood human organ and arguably one of the more important, not only for the health of a woman and her fetus during pregnancy but also for the lifelong health of both.” In May, the institute gathered about 70 scientists at its first conference devoted to the placenta, in hopes of starting a Human Placenta Project, with the ultimate goal of finding ways to detect abnormalities in the organ earlier, and treat or prevent them.

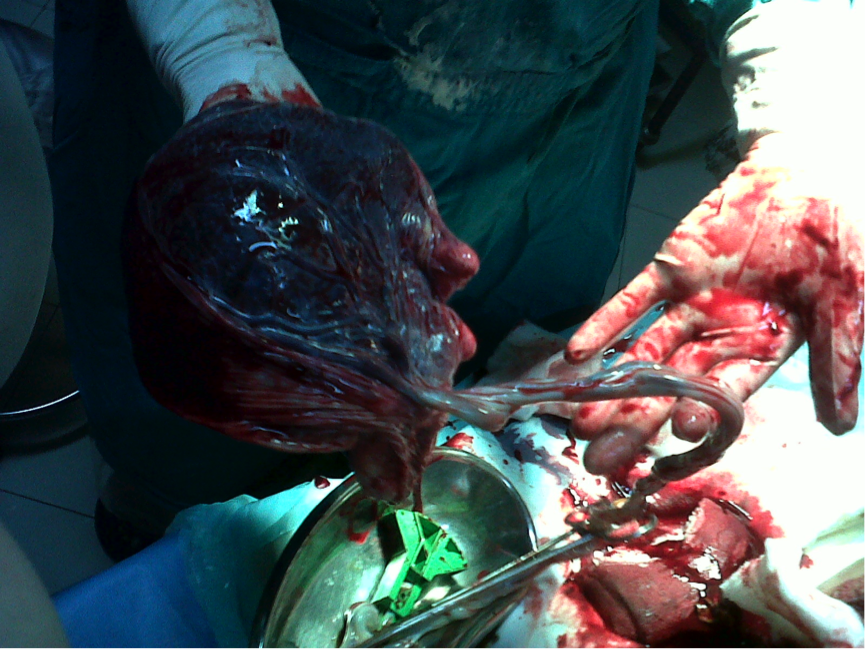

Seen shortly after a birth, the placenta is bloody and formidable looking. Fathers in the delivery room sometimes faint at the sight of it, doctors say. It is bluish or dark red, eight or nine inches across and about an inch thick in the middle. The side that faced the fetus is covered by a network of branching blood vessels, the umbilical cord emerging like a fat stalk. The side that faced the mother, glommed onto the uterine wall, looks raw and meaty.

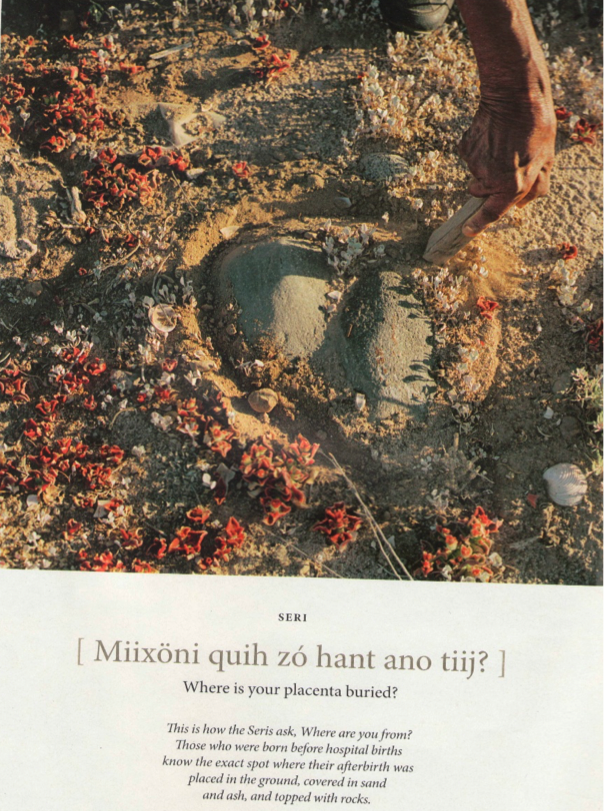

In some cultures, the organ has spiritual meaning and must be buried or dealt with according to rituals. In recent years in the United States, some women have become captivated by the idea of eating it — cooking it, blending it into smoothies, or having it dried and packed into capsules. Not much is known about whether this is a good idea. Audio

When scientists describe the human placenta, one unsettling word comes up repeatedly: “invasive.” The organ begins forming in the lining of the uterus as soon as a fertilized egg lands there, embedding itself deeply in the mother’s tissue and tapping into her arteries so aggressively that researchers liken it to cancer. In most other mammals, the placental attachment is much more superficial.

The placenta usually emerges from the mother’s body after the baby is born. It is a bloody messy organ that has sustained the infant’s life in the womb.

A small clay image of a girl child in a winnowing basket—it was a common practice in agricultural areas was to place a newborn in a winnowing basket after birth. This acknowledges the fertility of both women and the earth. Here you can also see the placenta still attached to the baby via the umbilical cord.

The umbilical cord, or part of it, was often kept when dried. Here a girl examines her own cord, kept carefully by her parents.

In Himachal Pradesh we heard from one dai that the dried cord was kept and put in a young man’s turban when he dressed for his marriage. It is as though the magic of fertility was passed from one generation to the next.

An image of the place where a placenta was buried—covered with a rock and flowers. The indigenous community in Northern Mexico would enquire where a person was from asking “where is your placenta buried?” This photo was taken from the National Geographic Magazine.