MATRIKA is short for Motherhood and Traditional Resources, Information, Knowledge and Action. It was a 3-year research project on traditional Indian midwifery in collaboration with four NGOs in North India. We came together to generate and analyze data gathered from workshops, role-plays, interviews, folklore and songs.

Traditional methods are not being used today because of the widespread belief that obstetrical (pharmaceutical, technological, surgical) methods are the best way to make birth safe. The Government of India has a policy of institutionalized birth for all—although institutions providing quality care are not available for the majority of Indian women.

Global health establishments (World Health Organization, Unicef, and bilateral funding agencies) have accepted the emphasis on “skilled attendance” at birth—meaning bio-medically skilled (able to read and write and use pharmaceuticals) not indigenously skilled.

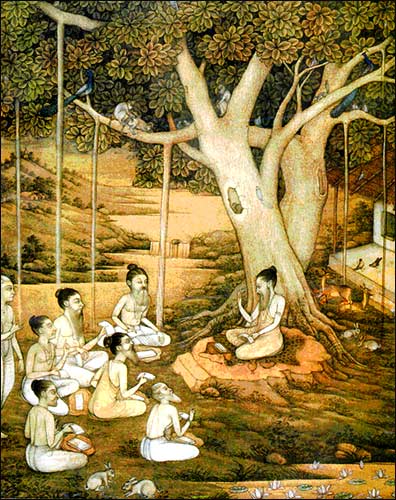

MATRIKA departed from the conventional Dai Training model. We asked the dais to train us in their own ways of handling pregnancy, birth postpartum. The MATRIKA perspective views women, specifically dais, as decision-makers within a different cultural and socio-economic milieu. Birth traditions, however, are not static and now unfortunately injections are replacing rituals.

Our research method stepped out of the allopathic and public health model of the female body and into the realm of indigenous cultural understandings.

We interacted with dais, asking them to share with us their own ethno-medical knowledge. Skills sharing and capacity building efforts of conventional dai training are often limited because the trainers have little understanding of the cultural context-dais mappings of the body and rituals, beliefs and attitudes.

MATRIKA has assembled a data base of therapies used by dais and other traditionally oriented women.

Women’s reproductive health initiatives have often critiqued top-down, hierarchical medical-delivery systems. In India culturally appropriate, affordable and gender-sensitive perspectives can only be implemented when health care providers and trainers have an appreciation of existing local health knowledge and practice. Assumptions that dais and women are ignorant about their bodies, and superstitious in the rituals which surround pregnancy and birth, work as barriers to effective and sustainable learning. .